Reclaiming Vancouver

Why building a big island in the middle of English Bay is the solution to all problems

I’ve written about this before, but no matter how many times someone says “build more housing” it just doesn’t get done.

The trouble for Vancouver is that it is in a bit of a unique position:

It’s full. It’s the 4th most dense city in North America behind NYC, Toronto, and SF.

More people want to come here. Vancouver is one of the most beautiful cities in the world and Canada is one of the most appealing immigration destinations in the world.

There’s no place to go. There’s no huge surrounding suburbs connected to it. There’s nowhere new to connect to or green fields to develop. Mountains block us to the north (and eventually east), the ocean to the west, and the border to the south. Toronto has multiple massive transit projects connecting different regions, but nothing like that is possible here.

Every time I go somewhere else, I’m always amazed at how much more room they have. This is something Vancouver simply does not have. You need to drive 1.5 hours to get to Langley or Abbotsford and even there, all of the land is either being rapidly developed or used as farms.

Vancouver is where it is because that is the only place it can be.

Largely, this has meant that we build up. As of July 2024, Vancouver is 3rd for the number of buildings with 10 or more stories under construction.

Even this will reach its limits. It is harder and harder to add new houses in areas where there is already density. For example, a group of planners and developers petitioned against the Broadway plan as they claimed it would replace “thousands” of older affordable units.

It might be time to take some more unorthodox approaches. One high on the list to consider: reclaiming land from the sea.

Vancouver’s history of reclamation

This may immediately strike you as something that only super-rich (UAE) or underwater (Netherlands) countries do, but the Vancouver we live in today has been completely shaped by it. Did you know False Creek used to run all the way to Clark Drive?

In 1912, Canadian Northern Railway negotiated to drain the eastern end of False Creek for railway lands. In 1917, it actually happened and became the home of Pacific Central Station. Afterwards, buildings like sawmills dominated False Creek and set it up to be the center of industry in Vancouver.

Later, the north shore of False Creek was reworked for Expo 86. The rail yards and lumber mills were removed, setting it up for the post-Expo redevelopment. This was done by Concord Pacific in “Canada's biggest master-planned urban community” featuring over 10,000 homes (and they’re not done).

Beyond these:

A network of creeks throughout the city (pictured above) have all been lost.

Multiple areas along Burrard Inlet, adding up to 945 hectares (2x Stanley Park), have been filled in over time. The major port terminals, oil refineries, and industrial facilities are all built on reclaimed land.

Richmond needed to build dikes because of how low it lies. Large sections of industrial land now sit on reclaimed land there. On top of this, parts of the aptly named Sea Island, where YVR now stands, were underwater before the airport was built there.

Granville Island, one of Vancouver’s most famous attractions, was created in 1915 by filling in a sandbar with 760,000 cubic meters of dredged material from False Creek.

There was a proposal in 1912 to basically turn Burrard Inlet into a lake with a dam and series of locks. This would have dramatically changed all the connected communities including creating a canal through Coquitlam. Instead, the Second Narrows road and rail bridges were built.

Why stop? Reclaiming Vancouver 2

The idea to continue reclaiming land in Vancouver has been considered nothing but a joke to most, but why? The housing crisis Vancouver faces isn’t a joke.

Of course, modern land reclamation projects face huge roadblocks in the form of regulation, environmental protection, NIMBYism, and cost, but we should at least consider it.

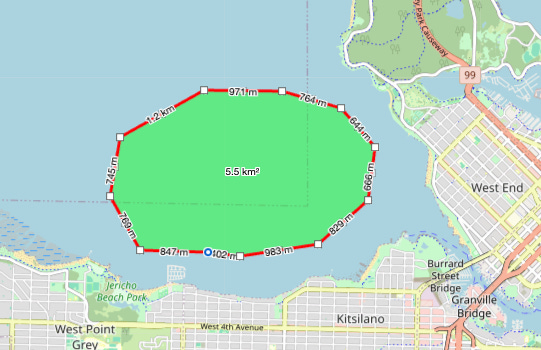

What if we build a new big island in the middle of English Bay? Connect it with a couple of bridges or tunnels to downtown and Kits. Something that looks like this:

The benefits of this would include:

New land means no old houses, noise problems, “neighbourhood character,” view cones, or shadows to deal with.

Can be built to be dense, walkable, and transit-oriented from the start. You can even build some new parks and beaches for people to use.

Prevents sprawl throughout the rest of Vancouver and BC. Enables us to protect the environment better elsewhere, less need to ruin other parts of the province to give people the housing they need.

English Bay is already polluted and has high levels of marine traffic, meaning a new development there would have less environmental impact.

Creates more density in downtown, leading to a more productive and vibrant city without adding traffic to current commuting routes.

English Bay is relatively shallow making it easier to reclaim land there.

Water for paddler boarders, pleasure crafts, all the rich people with waterfront properties so they can’t get mad.

So what about those big challenges?

Challenge one: regulation

Of course, reclamation will have a major environmental impact to whatever ecology is left there now. Environmentalists will use this to block the project, but they do that everywhere else too. Buildings, bridges, tunnels, and other infrastructure still manages to get built in Vancouver.

Indigenous groups have shown the way towards building big, ambitious projects in Vancouver. The Jericho Lands project is indigenous-led and one of the biggest new housing developments in Vancouver history. Getting the right group of stakeholders who want to create a radically better Vancouver could push this forward.

Challenge two: cost

It will cost a lot. As shown by the wastewater treatment plant saga, Metro Vancouver seems happy to waste billions. There are ways to make the math work, especially if regulatory costs and risks are lower.

We can figure out how much it would cost by looking at similar projects:

Singapore's recent land reclamation projects cost $270-850 CAD per m²

Dubai's Palm Jumeirah reclaimed 5.6 km² at a similar depth for approximately $2,893 CAD per m² (fully developed)

Hong Kong’s recent project to reclaim land for their international airport was reclaimed for $5,734 CAD per m² (fully developed).

Based on these and other similar projects, Claude calculates a 5.5km2 island at a depth of 25 meters would require 151.25 million cubic meters of fill. It estimates this would cost

$2.23 billion to $7.01 billion CAD based on Singapore’s reclamation costs.

$15.91 billion CAD based on Dubai’s reclamation and development costs.

$31.54 billion CAD based on Hong Kong’s reclamation and development costs.

Yes, these costs would be absolutely humongous. Site C is the largest public works project in Canada and has an estimated cost of $16B. The biggest in Vancouver is the Iona Island Wastewater Treatment Plant at an estimated $10B.

Looking at it another way, if the new island had similar lot sizes to downtown (1,700 m²), they would cost:

$459,000 - $1,445,000 CAD at Singapore prices (reclamation only)

$4.92 million CAD at Dubai prices (fully developed)

$9.75 million CAD at Hong Kong prices (fully developed)

If the island had the density of the West End at 15,659 units per km², this would put land costs per unit at:

$17,242 - $54,281 CAD per unit at Singapore prices (reclamation only)

$184,747 CAD per unit at Dubai prices (fully developed)

$366,173 CAD per unit at Hong Kong prices (fully developed)

This may be too big of a number to swallow, but big problems require big solutions.

Challenge three: name

Unfortunately, all of the good names for this potential island are taken: Vancouver Island, New England, Granville Island, Sea Island. We’ll figure something out. Feel free to drop some suggestions in the comments.

Other places are doing it, why aren’t we?

Some modern land reclamation projects include:

Palm Jumeirah in Dubai which reclaimed 5.6 km² in the early 2000s.

Nanhui New City in Shanghai which reclaimed 133.3 km² from the sea between 2003-2006 for 40 billion CNY which would be about $8.32B CAD in 2025 dollars.

Jurong Island in Singapore which merged seven smaller islands through land reclamation, totalling an area of 30 km² for $12.8 billion CAD in 2025 dollars.

Saemangeum Seawall in South Korea which built the longest man-made dyke of 33km, reclaiming 401 km² of estuary for $3.78 billion CAD in 2025 dollars.

Le Portier in ultra-pricey Monaco which is reclaiming 0.06 km² for a proportionally huge $3.38 billion CAD in 2025 dollars.

Going further back, New York, the Netherlands, China, Mumbai, Tokyo, Hong Kong, Montreal, Toronto, and many more places undertook massive land reclamation projects that are now a core part of their location.

Looking at the list of places that undertake land reclamation projects, you see some of the most important and productive cities and regions in the world. The fact that they needed to reclaim land and succeeded in doing so may reveal what’s needed to become the globally successful place that Vancouver has the potential to be. Land reclamation is proof of a combination of state capacity and ambition. It shows that humans can shape the world to their will. If Vancouver wants to join this group of globally successful mega cities, land reclamation might be a key part in doing it.

Love your vibes and thinking outside the box. But this is not a great take.

Vancouver isn’t full, the downtown peninsula is.

Most of Vancouver is still SFH. Fire up a real Vancouver Plan with permission to build up and LFG!

Interesting idea. I doubt the location would work as it ruins great sunset views from Sunset Beach, English Bay, etc. And too many rich & influential people live along that Kits shore to sign off on having their view ruined. BUT, an extension half the size in a different part of coastline could work. Like south of Wreck Beach.